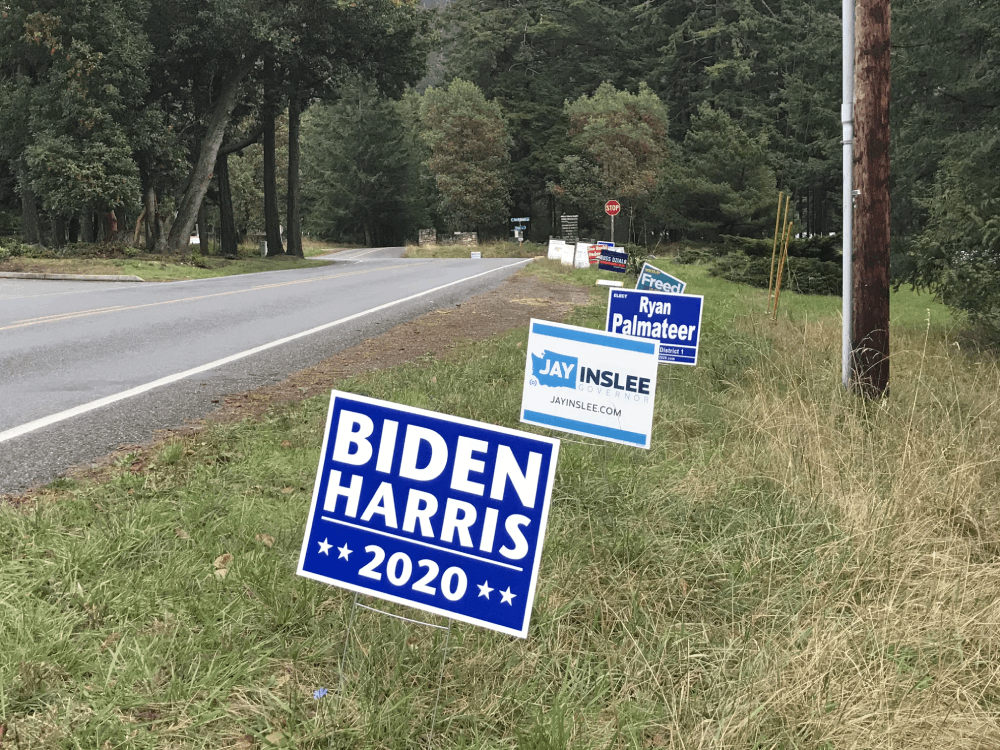

Political signs litter the Orcas streets / Photographer: Ellie Wright

This year has been eventful. 2020 came to yet another climax this upcoming November in the form of the presidential election. This election came with unusual challenges, but not entirely new ones. A century ago, during the Spanish flu, we also faced an election during a global pandemic. Democratic President Woodrow Wilson was fighting to keep control of Congress in the 1918 midterm elections, and conducted what the papers said to be “the first masked ballot ever known in the history of America.” Now, in 2020, we have experienced our second.

This is not to say that we are under the exact same circumstances. In 1918 the United States was in the midst of World War 1, which had raised patriotism among all political parties. Posters of Uncle Sam reminding Americans that “coughs and sneezes spread diseases, as dangerous as poison gas shell”’ were hung. Despite the patriotic sentiment of the nation, voter turn- out was still low.

“Voter turnout was lower than it had been previously, by about ten percentage points,” said Alex Navarro, assistant director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan, in his research that recounts the 1918-1919 pandemic. This could also be due to the war, since so many soldiers were overseas, and women did not yet have the right to vote.

The solution that was widely accepted was to lift the strict stay at home orders right before the election, allowing the candidates to campaign, and let the voters get to the polls. But this decision came with a cost.

Some saw risk in this choice of action, and protested the idea. Poll workers in Oakland, California, refused to show up. There was a case from Spokane, Washington, on the day before the election. Three people died from the flu, the most influenza deaths that the city had seen in one day. This sparked some panic among the voters and workers alike, and polling booths were moved outdoors and guards were stationed to prevent overcrowding.

These panicked voters and workers were right to be afraid. “The disease appeared to be reaching a significant amount of the population, greater than ever before; and the timing coincides with the lifting of the quarantine,” said Dr. Kristin Watkins from the University of Nebraska Medical Center in her research on the effects of the 1918 influenza pandemic on rural Nebraska. “The political machine disregarded the health and safety of its citizens.”

As the second wave of the disease spread the winter after the election, it was often difficult to track the spike in influenza numbers back to the election. This was mostly an issue in big cities. In smaller towns, the impact was much more observable. In her dissertation, It Came Across the Plains: the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in Rural Nebraska, Dr. Watkins details numerous cases of rural towns with previously limited numbers of influenza cases that spiked in the weeks following the election.

Another difference between the current election and the one held during our last major pandemic is a more widespread mail-in ballot system. Nowadays, we have the liberty of casting our ballots from safely inside our homes.

One instance of a state that has been hosting universal mail-in voting for years is Colorado. Since 2013, Colorado has offered mail-in voting to every one of its residents. Their mail-in ballot system has seemed to work very well for them over the years. Former Homeland Security Secretary Kristjen Nielsen said Colorado’s system “is an example of what other states can adopt.”

The state has one of the highest voter turnout rates of anywhere in the country, and this method has also proved to be more cost-efficient. Their election costs decreased by 40% after switching to universal mail-in voting, according to a Pew Charitable Trust funded study.

The state government takes care to make sure that the mailing lists maintain accuracy using data from the Colorado Department of Revenue and other sources. The voter registration lists are also cross-checked against the Social Security Index, which removes people who have died from the voter’s list. They also check that the signature written on the ballot matches the one they have on file, which is typically pulled from your driver’s license. Colorado Secretary of State confidently claims that only 0.0027 percent of the 2.5 million ballots cast in the 2018 midterms are suspected to possibly be fraudulent.

Colorado’s mail-in voting system shines a promising light on the idea of mail-in voting, but some still have their worries. Many states that do not have all the safety precautions that Colorado has in place have been forced to scrounge up a remote voting system in time for the election. This leaves lots of room for error, such as out of date voter registration lists, and a lack of identity confirmation.

The chance of these errors causes some to fear that fraudulent votes will be cast using the mail-in ballots. President Trump himself stated on Twitter that “With universal mail-In voting… 2020 will be the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT election in history.” There is unease among some voters as well.

Others, such as presidential candidate Joe Biden, assure the country that “Voting by mail is safe and secure.” These voters have hope that all the remote voting will run as smoothly as it has in Colorado.

In the past, there have been cases of voter fraud by mail-in ballots. A voter fraud database collected by Arizona State University finds only 491 cases of confirmed fraudulent voting by postal ballots. Oregon has held remote voting since 2000, and have only reported 14 invalid ballots. Then again, this was mail-in voting on a much smaller scale than will be attempted this year, which could change the level of voter fraud.

Mailed ballots have been sent out at a scale that has never been done before. It is still yet to be seen what the effects of this election will be, and if we have learned from the outcomes of the 1918 midterms. But no matter who wins this election, it is one that will go down in history.